By Jeffrey Watson Potter - Sold to Bicycling Magazine, 1996

By Jeffrey Watson Potter - Sold to Bicycling Magazine, 1996

Frankly, I was worried when the Chinese Military Police arrived at the cafe in Tibet; I knew there was no way that we could escape unnoticed. While imagining my confession (expired and improper papers, entry in a restricted area of Tibet, illegal means of transport), I began to doubt the sanity of bicycling the 5000 + kilometers from Kathmandu, Nepal to Beijing, China. Less than a week into the trip, and I was headed for jail.

I've never been one to believe in omens, but in hindsight, the road was littered with them. On the second day of the ride my right front pannier came flying off on a fast descent, tumbling over itself, and nearly passing me by as it seemed to be picking up speed. I replaced a lost lock arm washer with a whittled out guitar pick.

Then, inexplicably, Tom lost a rear pannier on the road, never hearing it detach itself and drop onto the road, all his film, our Tibet guide book, and his tools were never found. Finally, there were the Swiss.

We met them on the road after backtracking, looking for Tom's pannier; two big guys on cranky black bicycles. One was wearing sandals and the other, combat boots. They were desperate looking fellows, at the tail end of a Hong Kong, Tibet, Kathmandu trip. Tom and I shared a glance and both wondered, had we seen our future? The next day we hit the border . . .

Some young soldiers noticed our bikes parked away from the visa office, and gathered to examine them. Tom's leaned against mine, absorbing the groping hands. Almost immediately a soldier straddled Tom's bike - and there was nothing we could do.

Before we knew it, he was off, and out of control - the brakes, the gears, the suspension fork were foreign to him and he skidded to a halt, nearly throwing himself. Another soldier made a move for my Trek. I reached the bike just as he discovered the quick release to lower the seat.

"Too big!" I pantomimed with my hands, shaking my head.

"Lower the seat for me so I can ride it, you dope!" he motioned back.

"Sorry. Ha ha. Too big." I signed again, smiling, slipping away.

When it came to playing dumb in China, I was an Oscar contender.

Back at the cafe, I hadn't even a chance to slip into character before the commanding officer returned our expired papers with a smile.

"Have a nice day." he said, in nearly perfect English.

We were too stunned to respond, still haunted by the possibility of imprisonment and forced labor in the Chinese coal mines.

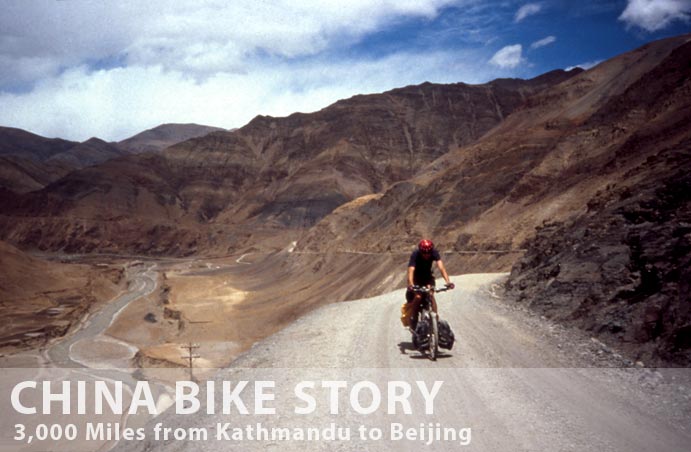

When I hatched this scheme back in '95, the plan seemed simple in conception, though admittedly difficult in execution. On completion of my Peace Corps contract in Nepal, I would bicycle from Kathmandu, to Beijing, China; across the Himalayas, the Tibetan Plateau, through the northern deserts, along the Silk Road and Yellow River, dipping down through Xian, and then north to Beijing. A 3000 mile journey, with the first third along the highest road in the world. Joining me in the beginning of this journey was Tom Robertson, a good friend, and fellow Peace Corps volunteer.

Since there is only one north-south road through the heart of Tibet, our route was simple enough; all we carried was a National Geographic map of China and a few photocopies from an atlas.

(Italics are journal entries/breaks)

At times I feel like I might lose my mind. The wind is relentless, chapping my face, running my nose, and filling my ears with the sound of white noise. The landscape is a lifeless desert, broken by hills and mountains in the distance, We have not seen a tree or even a shrub since the Nepali border. I think the whole plateau is above the tree line, above 4000 meters.

We stayed with families when we could, but the plateau is sparsely populated. The families that would even take time to listen to us were obviously cautious about associating with westerners. The years of oppression by the Chinese government have created a sense of distrust in many villages. We found it difficult to meet people and if they invited us to stay, it was usually in the yak pen, away from the house. Quite often we camped.

The mornings were cold. We woke up with frost on our bikes and the yaks. They were kind enough to let us share their space for the night, and thankfully they appeared to be as nervous about us, as we were about them.

Amala (mother) came down from the house carrying our morning breakfast. As I tried to thaw my frozen water bottle, Tom made small talk and stirred his tea. It is peculiar stuff, this Tibetan tea, called poja - made from yak butter, salt, hot water, and occasionally, tea. It makes up half of a common meal on the plateau.

Tsampa, the other half, is a bland roasted barley flour, that would not rank well on the USRDA scale of nutrition. Mixed with poja, it creates a paste, not dissimilar to those eaten and enjoyed by grade schoolers throughout the U.S.. Although it was comforting to find such a familiar delicacy available this far from home, I was not ecstatic about riding 90 km days while living on this stuff. I rationed my packets of instant breakfast drink and dreamed of power bars.

Thankfully we never went more than three meals in a row on tsampa and cha. Small diners selling a noodle soup called thukpa, ting momos (steamed rolls), and in bigger towns, Chinese food, were not uncommon as we neared Lhasa.

Nearly 70 km of paved road welcomed us into the capital city, encouraging us to ride into the late evening and arrive in the falling light. From the outskirts of town, we could see the Potala Palace, the 700 hundred room landmark that once housed the now exiled Dalai Lama's government.

Chinese industrial sprawl gave way to squat stone buildings as we neared the heart of this ancient city. We passed the 1300 year old Jokang Temple, perhaps the holiest shrine in Tibetan Buddhism, and the street crowds thickened with pilgrims. Hawkers plied their wares on unsuspecting villagers and the occasional tourist making their clockwise circuit on the Barkhor, the periphery of the Temple. Down the block we found a hotel, happy to fill its last room for the night.

With seven days to rest, refuel, and clean up our bikes, I had plenty of time to take some side trips to monasteries, nestled in the hills surrounding Lhasa. At Drepung Monastery, hoards of Tibetans had gathered to hear a Bodhisattva teach. In Buddhism, a Bodhisattva is a person who has achieved enlightenment, but out of compassion delays their entry into Nirvana, in order to stay behind and teach the rest of us.

The Bodhisattva spends his days meditating, as much as 16 hours, seven days a week for 49 weeks. Each year he teaches for three weeks, and this was the last day before his return to seclusion. Although I didn't speak Tibetan, I was sure that this was not to be missed. I clambered into the back of a truck with a crowd of villagers, monks, and a few tourists for the 7 km ride to Drepung.

The sprawling complex of buildings was teeming with activity and I could barely make my way to the main hall where the Master sat. Anyone who attended Woodstock, would likely feel a sense of deja vu looking down upon the colorful hats, clothing, and flowers adorning the tens of thousands in the audience.

The calm and patient listening of the crowd was a testament itself to the spirit of the moment, but when young novices from the monastery appeared with large wooden vessels to serve tea to everyone I was dumbstruck. And old Tibetan man offered me an empty cup, just before a novice came our way with the tea; I nodded appreciatively and we drank together in silence. It was a lasting moment of peace before heading back on the road.

There are three words for dog in the Lonely Planet Tibetan Phrase Book: kiy, meaning a simple, cute, fuzzy kind of mutt; shakiy, a hunting dog most valued by shepherds; and dokyi - guard dog, the biker's worst enemy and, incidentally, the most common dogs around.

Tibetan Buddhism teaches reincarnation, that a person continues returning to earth, reborn in many forms, until they can reach enlightenment and pass on to the other side. This is the basis of the religion's famed compassion and the belief that all life is sacred. Squash that roach and you may be squashing your long dead Great Grandfather.

Dogs are believed to be special incarnations in this chain, and thus are given a very high status. Mangy mutts, the lovable kiy , are often seen roaming around monasteries, living a luxurious life under the care of the monks or nuns therein. On the road, it is an entirely different story. Every house, worksite, and blind corner could hide the evil dokyi.

As we neared the top of the 4900m Kyogoche pass leaving Lhasa we could see the prayer flags, a welcome and familiar marker signaling the end of the climb. The forty-five minute crawl forced me into my grannies thanks to the 90 pounds of bike beneath me - I had kept my cadence, but had lost my speed. Now, seeing the top, I could sit up a bit and stretch my sore neck. That was when I saw them.

Three dogs, sum dokyi, Tibetan Mastifs, were barreling down on Tom about 100 meters ahead. Before I could shout, he saw them and laid on his shifters. He was standing off his saddle and shouting, cursing at the beasts. I was sure he'd be dokyi dinner, but somehow he shook them and they gave up. He'd made it to the top. Then they turned and saw me.

I quickly dismounted, grabbed a handful of rocks from the road, and tore the velcro restraining strap from my mini pump, "Bloody mini-pumps!" I thought, cursing the gramheads who had designed such a useless weapon.

As the dogs raced the hundred meters back toward me, I remounted and geared up, standing in my saddle and forcing every bit of speed I could from my legs. My plan was to meet them running and blow right by them, but they must have anticipated that, for they stopped in their tracks. They were waiting for me to come to them - conserving their energy!

By the time we met, I had slowed to a crawl (racing at 16, 000 + feet and cursing at pump manufacturers must have soaked my last adrenaline). I began heaving rocks at them as I rode by, screaming bloody murder. One of them backed off immediately; the second, when pegged with a small stone, kept his distance, but the third was determined - perhaps the reincarnation of my Great Grandmother.

Grandma or not, I had run out of rocks and considered heaving my pump. I thought better of it and pulled my water bottle, spraying the closing canine right in the snout. It wasn't pepper spray, but it worked and I broke free. The dogs returned to the fifth level of hell, or wherever they came from. Tom and I collapsed at the pass, intermittently laughing and shaking before enjoying the race down the other side.

North of Lhasa, the population thins, the plateau rises, and a kind of desperation settled in. Rolling hills, barren and bright, reflected the light of the overpowering sun. Even gentle slopes forced us to gear down and tuck into the wind. We faced 4,500+ meter passes daily, and we still seemed to be climbing as we headed into the Tanggula Mountains that are the southern border of the Qinghai Province. Crossing the pass at 17, 521 feet we paused to appreciate the highest road in the world, and say good-bye to Tibet.

As I struggle up these slopes I am reminded of the nun we met some 300 km north of Lhasa, crawling on her stomach, prostrating in pure faith on her pilgrimage to the city. I try to forget the pain in my legs, imagining that the sound of the gears is the sound of my legs - I am a machine. My mind wanders. It fills with a kind of dramatic joy when I'm riding, a meditation, thinking of home. I am in Qinghai, China - nowhere - a Siberia for convicts and exiles where goulags still exist.

Eleven days and more than 1100 kilometers from Lhasa, we were in Golmud - a place from which the Lonely Planet said "Hell is a local phone call." Having just rode in from hell, we were pleased to be anywhere with hot showers, plentiful food, and a place to stay the night.

Golmud is a fascinating city. Drab, stalinesque buildings sit on wide boulevards lined with young trees struggling against the desert sand storms. The sidewalks play host to merchants selling all varieties of dried fruits and nuts, upstart entrepreneurs of the new China; outdoor pool tables are ringed by enthusiastic spectators and players.

Perhaps more than any other city in the region, Golmud reflects the diversity of northwestern China. The indigenous Tibetans, the remnant and resilient Silk Road Persian Muslims, and the immigrant Han Chinese from the east all live side by side in this outpost, many of them working in the area Potash Mine, one of only three operating in the world.

Just three days East of the city Tom and I split up. Differing schedules and pacing forced us apart. He joined up with an Englishman we'd met and I went on alone. With my father's June wedding looming, I took inventory of my progress. I had a month to reach Beijing, more than 2500 km away.

Traveling alone definitely has its advantages. Moving eastward into China my pace picked up, I averaged more than 120 km/day, often riding less than 6 hours. Coming out of the desert and into China proper, the altitude dropped, but the rolling hills continued.

The population was denser in Gansu Province and my tent had become dead weight as I stayed most nights in truck stops along the road. These government operated hostels were Spartan, but comfortable, and the 15 Yuan price (about $2.00) was a bargain. Food was plentiful and equally cheap here.

As a vegetarian, dining out is sometimes difficult for me in a America. But I had even more trouble in China, where diet and dialect seemed to conspire against me. At first I tried the guide book's suggestion, just walk into the kitchen and point to what you want. "No problem," I thought.

At a restaurant in Dingxi, I walked into the tiny, "well seasoned", well stocked kitchen. The cook, who looked like a thin, Chinese version of Al from TV's "Alice", didn't seem to mind my being there. As if on cue, he began to show me around, pointing out different ingredients.

Everything looked fresh and inviting, even mysterious. Maybe too exotic - the cabbage was one of the only things I recognized and sadly, a cabbage and rice stir fry wasn't what I was longing for.

"Wo chi-su", I said, trying out my virgin Chinese.

The cook, Al, motioned to the meats, "Is this what you want?"

"No, no . . . I . . ." I hesitated, trying to think of what to say.

Al, sensing that I had an objective, began to point at all the ingredients in the kitchen: "A lifeless fish?"

"No, I. . . no", I shook my head.

"This bloody leg of animal? This amorphous meat broth?"

"Wo chi-su", I tried again.

He looked at me bewildered, then muttered something to himself and turned back to his cutting board. He began chopping at the leg of meat.

Al was quickly growing tired of me and if I was going to eat anything, I would have to fetch the phrase book and pray for the literacy that China is so famed for.

"Wo chisu.", I said pointing to the phrase in the book, "I am vegetarian."

Al smiled and his frustrated expression vanished.

"Sude!?", he smiled, pointing at me.

"Yes, yes!", I replied, patting him on the back, not understanding him, but sensing he got it. He did, and like countless others in China, he was an excellent cook.

The next day I hit my first flat. After 2000 miles without trouble, I was due for a little. As nearly everywhere I went, a crowd gathered to watch the ridiculous lowai (white devil) in action.

I had been warned that my Continental Town and Country tires had a snug fit, but the struggle to seat it in the rim after patching the tube, left me with another puncture and a crowd of on-lookers growing in size and curiosity.

One has to remain cheerful in Asia while not encouraging those who assume the role of stalker: following your every move; fielding all questions; and generally breathing down your neck - or in this case - my neck. However, in this case, the stalker had strong arms, and like most folks in China, he was no stranger to bicycle repairs. A new patch, some Pedros on the rim, and a little help from my new friend put me back on the road in no time.

I'm staying in the home of a school teacher here in Biyu. He had the only place known as a "hotel". It is one room of the house, where I had to pay a bit extra not to share it with three family members. Ironically, I was wondering today on the road if I would ever see the inside of a village home.

A young middle school student helped me find the teacher. He spoke English poorly, but wrote rather well, so we had a lively discussion on paper before we went. On my own for nearly two weeks now, I was hungry for interaction; it really made me feel more connected here. The winds were whipping up a storm and I was eager to find a place in this traditional village.

The winds died down in the early evening, never bringing the feared storm. I closed the door to my small room and lay down by the window light to read a Jane Austin book I had bought in Lanzou (it's cover is in Chinese and therefore must convince onlookers that I can read their language) . The teacher's young son and his school mates were watching me in the window, whispering and giggling to themselves.

Occasionally an adult would join them, watching me in my fishbowl, until I glanced up - whence they would scold the children and continue on their way. With the adult out of sight, the children would return. Finally, exhausted, I reluctantly pulled the curtains closed in need of solitude.

The boys disappeared from the window, but could still be heard scuttling about the courtyard. I thought I heard some English words and some boyhood posturing before there was a knock at my door. The three of them stood in a row, one with a basketball in hand, the middle one staring up at my 6'5" height and proffering a note. In simple, shaky letters it said: "Go to play basketball?"

In spite of my exhaustion, I had to go. We went together, trooping through town on the dusty lane to the school where teachers and students alike were shooting hoops in the falling light. It was fun and the kids were quite good.

That evening, as I finished writing in my journal the teacher's wife brought in a small, square, low legged table which she placed on my bed. Her husband, their two kids, and their grandmother followed carrying a large steamed bread, stir fried potatoes with onions, and chopsticks all around.

We ate by the light of my reading candle, nodding and occasionally smiling at one another. The simple, slightly spicy, but very good food was the focus of our attention - my exhaustion had been usurped by a wonderful feeling of peace.

Had I known what lay just a few days ahead of me on the road, I may not have wanted to leave the next morning. I was nearing the edge of my Nelles map of Northern China, but I still had the National Geographic map that gave me the big picture. From where I was, it looked simple enough - head due east from Tianshui to Baoji and then on to my next big destination, Xian.

Although I couldn't see a road on the Nat'l Geo map, it seemed fairly obvious to me that two large cities like Tianshui and Baoji would most certainly be connected by the shortest possible route, about 180 km by my estimation. Had I wanted to stay on my map, I would have to backtrack, and circle on a northern route to this eastern destination, maybe 370 km. The choice was obvious, right?

Just outside of Tianshui I hit a checkpoint. These were uncommon in the east and the first I had seen since Tibet. I casually rode right on through without a problem, but soon after hit a fork in the road. Not knowing which path would lead me north and which would lead me east, I waved down a passerby.

"Baoji? Baoji lu?" I said, trying to smile and look lost (which was easy).

A woman stopped and looked at me.

"Baoji? Wo qu Baoji." (I am going to Baoji.) This time I made pedaling motions with my hands, then tapped my bike, smiled and pointed the road ahead.

She took one last look at me and walked on. This was a tough audience. After a few more feeble attempts, I turned around and rode back to the police check post, praying they wouldn't see fit to detain me.

They watched as I approached, occasionally shifting their glance to the cars whizzing around them. I parked my bike and crossed over to their booth, this time with map in hand.

"Nihao!" (Hello!) I said, bowing slightly and smiling. "Wo qu Baoji. Zheige lu Baoji qu?" (I am going to Baoji. Does this road go to Baoji?)

The officer took my map, as I pointed to Baoji, repeating my question and smiles. Pausing for a moment he seemed to hesitate, then he said "Bu qu!" (No, it doesn't go).

I didn't trust him. "Why did he hesitate?", I thought. Perhaps there was a road there and he didn't want me to go on it. Maybe there were even military secrets he was protecting. I had heard of areas closed to Westerners, but had no idea where they were or how that status was determined. I changed my tactic.

"Baoji qu lu, shi ma?" (Is there a road to Baoji?), pointing again on the map, the straight route I was sure existed.

"Dui, lu shi." (Yes, there is a road) he said.

Now we were getting somewhere. There was a road there, but for some reason he didn't want me to go on it. Just then another officer came over and joined my man in the booth. They talked for a moment, pointed at me, and then turned back.

"Wo qu Baoji." (I'm going to Baoji), I said to the new man, this time with determination. I was certain that from the map and their reaction that the straight road was the one that I wanted. The second officer looked over at me.

"Ni qu Baoji?" (You're going to Baoji?)

"Dui.", I said.

He pointed to the long road on the left, "Baoji qu lu." (That road goes to Baoji.)

"Xiexie!" (Thank you!) I smiled, mounting my bike and riding off to the right hand road. "Thought they could trick me!" I laughed to myself.

About 10 km off things started to get bumpy and I began to understand. The road was under construction and not too pleasant. "Well, I made it fine along hundreds of kilometers of dirt roads in Tibet," I thought "How bad could it be?"

By mid afternoon there was no auto traffic on the road at all. Snaking along the Wei River, I could see trains passing by now again, the tracks running on the opposite bank. I was in genuine farmland, the northern grain belt of China. Construction trucks occasionally passed me by, honking and giving thumbs up, perhaps baiting me on.

After nearly sixty km I hit a dead end - a huge pile of boulders, mud, and debris left by a dozer on the road. Apparently the government was attempting to widen and pave the old country dirt road so that traffic between Tianshui and Baoji wouldn't have to go 200 km out of the way.

I dismounted and wheeled my bike around the debris, back onto a section of tolerable road. Less than two kilometers later I hit the first obstacle, a ten foot section of missing road. Gravel trucks and dozers had obviously worked to fill and level this raised section, but had not quite finished the job.

A group of workers laughed and pointed as I removed my gear from my bike, schlepping it all into the crumbling ditch onto the other side. The thought of turning back crossed my mind, but the unknown ahead had to be better than the known misery behind.

Another 10 km down the road I hit much more than a pile of debris left by a dozer. In an attempt to clear a new route for the road, crews had dynamited the side of a mountain, causing an enormous landslide that reached down to the river below. There was no way around it and I was stuck. I would have to turn back, but not without a rest.

I sat down on a pile of rubble and watched a crew of 15 men chipping away at the mountain. Before long they noticed me, and obviously surprised, came over to investigate. Exhausted, disheveled, and brokenhearted I repeated my mantra one last time, "Wo qu Baoji" (I am going to Baoji).

They laughed and shook their heads, sitting down around me, wiping their sweaty brows. A few of them examined my bike, kicking the tires and ringing the bell.

"Where are you from?" a man asked.

"He's from America." another answered, not really knowing. They looked at me and I nodded, "Dui, meiguo da."

I had resigned myself to turning around and heading back toward Tianshui, but at least, I thought "Let me get a picture of the rock that stopped me." I grabbed my camera and encouraged the workers to squeeze together, the brims of their bamboo woven hard hats touching one another.

"Smile!" I said, smiling myself at the scene.

Putting my camera away I turned to whom I guessed was the crew leader.

"Baoji?", I said pointing at the landslide closed road.

"Dui." He replied, yes.

Before I knew it, five of his men and I were gingerly making our way across the hundred meter rock slide. They had my bike and some bags between them, insisting on carrying them with me. With a set of panniers in hand, I scrambled ahead, trying to keep my weight low. Within ten minutes I was on the other side, still facing crummy roads, but over another obstacle and on my way.

It was late afternoon before I came across a bridge over the river. I crossed to a small town and found a room easily enough. After settling in and cleaning up a bit I went straight to the train station, determined to buy a ticket to Baoji and avoid the continuing construction. Although I kicked myself for giving in to some non-bicycle transportation, I still had a wedding to make and a good bit of country to see.

The woman in the ticket booth was helpful, informing me that 14 Yuan would take me and my bike the 2 hours to Baoji in the morning. I took out my wallet, ready to pay when she stopped me - I would have to come back tomorrow. Tickets are only sold before the train leaves. She gave me a schedule and sent me on my way.

I had some dinner and walked back to my room enjoying an ice cream bar. Just as I reached my room, it hit me - "There is no way I am going to give up now. The rest of the road may be fine and I'll have to watch it from the window of the train, cursing myself the entire way. This is a bike trip, not a train trip!" (See, goal oriented thinking is not always healthy.)

The next morning I was back on my bike, across the bridge and bumping along a torn up road, laughing at the thought of taking the train. Obviously that didn't last very long. Within the hour I had reached the mother of all landslides. A shear cliff had recently been blasted away, leaving a precarious pile of rocks on the road beneath it. There were no bamboo helmeted workers chipping away here, it was too dangerous for that.

Instead, two well dressed government foremen stood by their jeep watching a large back-hoe in action, scooping rocks from the pile and dropping them behind it to the river below. I rode up to the men, but they ignored me.

I laid my bike down and gestured to them. They looked at me, unimpressed, and continued to watch the back-hoe.

"Wo qu Baoji." I said. My mantra again.

The men looked at me and then pointed into the forest. There was a small path worn there and I traced it halfway up the cliffside before it seemed to disappear. "Could they possible expect me to climb that cliff? I'm a landslide man.", I thought.

Just then, at the top edge of the cliff I saw a man appear. He dropped down briefly, switching back, and then I lost him in the shrubs below; within five minutes he appeared out of the trees by the roadside. "Seems easy enough," I thought. I was wrong.

Starting with my bags I scrambled up the soft slope and made it half way, before dropping one of the bags. Watching it roll over itself, tumbling and crashing though the undergrowth I felt sick. I ran back down and fetched it, and doubled my effort to reach the top.

Once there, I gazed down at my bike and the back-hoe, sharing the precipice with a construction worker in a funky orange hat who was likely playing hooky from the foremen below. I pantomimed my adventure briefly and of course let him in on my little secret, "Wo qu Baoji."

We got up to leave together and without my asking, the worker grabbed a bag to help me down the steep path to the other side. After two more trips, with the bags, I prepared to take my bike over. It was awkward and I needed to have my hands free, so I carried the bike until the slope became too steep to climb without my hands. The last thirty meters I leaned into the cliff with my body, pulling myself up with one hand and dragging the bike by the front rim with the other.

At the precipice, I took off my belt and looped one end through the bike and the other to a carabiner on my waist; if my bike was going to go over the side on the trip down, I wanted to go with it. Thankfully we both made it, finding my bags waiting at the bottom on the unfinished road. I loaded up and said good-bye to the workers gathered 'round. As they shouted out and gave thumbs up (the international sign of excellence, of course!), I imagined my place in the history books: First Bicyclist to Ride New Tianshui-Baoji People's Super Highway Awarded Honorary Hard Helmet! "'Everything from here on out, a piece of cake.', says young American." Well, . . . almost.

Within two days I was in Xian, the first capital of China, settled nearly 6,000 years ago, and home of the terra-cotta warriors. As I rolled into the city, a long 200 km ride east of Baoji, it began to rain. "No worries," I said to myself, "I'll be here for days." But it rained, and rained, and rained.

It rained on the first day, when I did my laundry and cleaned up my bike. It rained on the second day, when I stood amazed, staring at the terra-cotta warriors; an awesome sight, as if the Grand Canyon had been dug by hand. It rained on the third day as I circled about the city, looking at Museums and wondering if it would ever stop. On the fourth day, I had planned to leave, but it rained, so I stayed in my room and read The Godfather - venturing out only to Mom's Place, the one of a kind western diner across the street.

On the fifth day, it rained, so I cursed and headed out into the downpour. I had suffered plenty of rain during the two monsoons I spent in Nepal, but riding in this was a new experience. I was drenched clear through, my front panniers deflecting water traps like the running boards on a 4X4. Most of my gear was zip-locked, but when I stopped for the night, I had to turn my panniers over and let the water run out. This kept up for seven days.

Road crews were tearing up pavement everywhere in the government effort to improve China's infrastructure and become a world economic power. The people, the cars, the capitalist spirit! Where was the China that I had heard so much about? The last, most totalitarian communist behemoth in the world? A country so full of software pirating, Hong Kong taking, one child having, godless killers, that they would someday take over the planet? Well, I don't know.

Traffic was picking up as I neared Beijing, but I didn't care, I was determined. I hit another block of construction, but was able to sneak through the traffic jam that was building up. When I got to the front of the line, I saw the problem: a crew had torn up both lanes of the road, imagining it would make for quicker work, but the rains had left a sea of mud in its place. Cars, trucks, and semis were sliding, getting stuck as they ventured into the muck.

I crossed my fingers and geared down, praying to stay upright and out of the 8 inch sludge - I didn't last long. Soon I was pushing my bike, intermittently stopping to rest and clean out the clogged cantis and fork. My fenders were packed with the stuff and the wheels refused to turn, I had to get off the road.

I made my way over to a gas station and got some water to free up the wheels and then was back on the road, pushing again. There was no shoulder here, only a flooded ditch and a barricade wall. "Still, better than that cliff." I thought.

A flatbed truck behind me began to honk, and I tried to wave him around. The driver pulled up beside me and slowed down, he gestured out the window,

"Get in, we'll put your bike in back!" He signed.

I waved him off, smiling. I didn't take the train and I had no intention of getting on his truck. He pulled ahead a bit and then stopped on the right. When I reached him, he came out onto the road. "Determined son of a gun." I thought. "Hope there's no trouble."

Instead of starting a fight, he grabbed my bike. There was no way I was letting go, but he didn't pull it from me, he started pushing with me! He leaned into it and together we slid the bike along the road.

He was a well dressed chap and I felt terrible looking down at his black tasseled loafers covered with mud - this was not an American truck driver by any stretch! I stopped and waved him off, smiling and thanking him again. He pointed at the truck with hope, but when I didn't budge, he shrugged his shoulders and slogged back alone.

Forty minutes later I was still in the mud. My legs were covered and solid ground was no where in sight. I had twice jammed chop sticks under the fenders hoping to free the wheels, but my minor successes were quickly quashed by a single mud packed rotation. I tried carrying the bike, but the weight of it upon my sliding feet nearly sent me to the road to wallow.

Sliding autos and semis around me weren't helping the matter, and when I heard another friendly honk behind me, I relented. It was a different driver, but with a similar flatbed truck. He got out and helped load me and the bike in back. He jumped in the cab and we were off. I was glad to be out of trouble, but felt guilty about the ride.

However, it didn't last long - within 500 meters we hit pavement. I had pushed my bike more than four kilometers and had just missed the end. I anxiously banged on the roof of the cab, not knowing or even caring the word for "Stop!". The driver pulled over and I thanked him repeatedly, while unloading my bike.

"Beijing?" He asked, pointing down the road.

"I can make from here by myself." I said. A week later I was in the city.

Well Bless My Soul and Kiss My Happy White Ass, I'm in Beijing!

Finally here, and exactly two months from the day I left Kathmandu,

Nepal. I rode straight to Tiananmen Square to have my photo taken.

Sadly, I didn't realize I was just a block from the big Mao portrait, so I had my photo taken with his mausoleum and the South Gate.

Having lived in New York City while in school, I felt comfortable in Beijing walking or riding the streets. The city is full of life, art, and business (like New York), but it is also clean; with plenty of parks; wide, bike filled boulevards; and virtually no crime (unlike New York).

One night I saw a traditional opera performed and then, later at a pub, I saw Cobra - China's only all female rockband. Quite honestly, I loved both shows, and back to back they said a lot about what's happening in this rapidly changing culture.

Although hostels were filled with tourists telling miserable stories about red tape, corruption, crowded trains, long lines, and paper work - not one of the handful of bikers I met had anything bad to say. As for me, I rode around with a ridiculous grin on my face.

In China, the Bicycle still reigns supreme: at the Peking Acrobats, I felt like a kid again watching eleven performers climb onto one bike and circle the stage (perhaps a sly metaphor for the troubles of population growth?); scattered along the highways are bicycle repairmen, working out of the back of tricycle pick up trucks (some even have super powers, I'll bet); and attended bike racks are more common than auto lots and parking meters (the "Wisdom of the East"!) It was a shame to have to come home; I think my bike still misses it. I know I do.